With a little time spent on TikTok or in a group chat with younger women, you’ll notice a trend: Gen Z public conversations about menstruation seem to be a matter of concern. If you are scrolling through this article and wondering why your cycle suddenly feels “off,” “weird,” or “all over the place.” I’d say this: your body is responding to the world you’re growing up in. Stress looks different now. Food looks different. Sleep is shorter, screens are louder, and expectations are heavier. Of course your hormones are trying to keep up.

What you’re seeing online, late periods, heavier bleeding, cycles that feel “off,” is not a personal failure or a mystery unique to just you. It’s a generational pattern. And while social media can make it feel alarming, it’s also doing something important: it’s finally giving women language to talk about what we were once told to ignore. So take a breath. Pay attention without panicking. Your cycle is information, not a verdict. And learning to listen to it now, without shame or fear, is one of the most powerful forms of self-trust you’ll ever build.

You may be wondering, “are Gen Z periods actually different?” The answer is “Yes” in many ways. Behind the trend is a pattern that seems to be understudied. And the reasons for this period difference are complex; biology, lifestyle, environment, stress, technology, and cultural transparency all collide to shape younger women’s menstrual health.

Emerging research reveals that one of the most noticeable generational shifts is early menarche, the age at which a girl starts her first menstruation. Girls are now starting their menstrual periods earlier than in previous decades (earlier than the average age of 12). However, earlier periods don’t automatically mean stable cycles.

Image: Pinterest

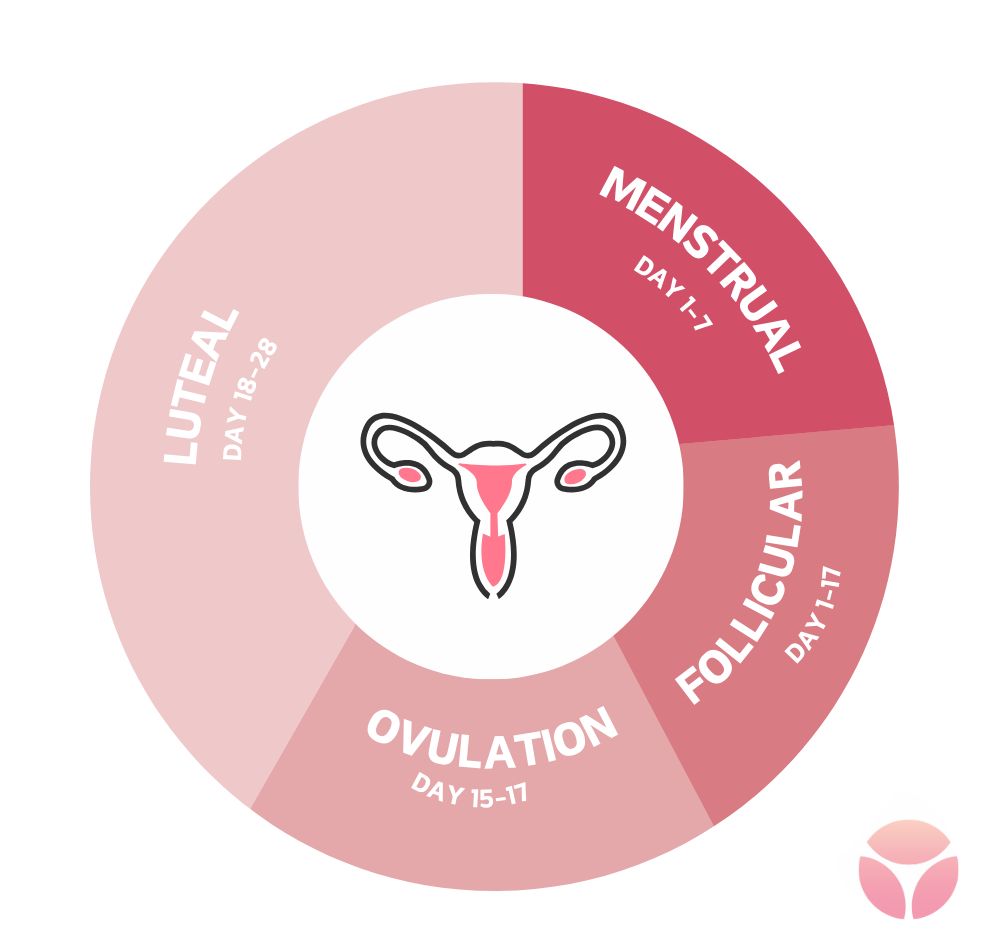

Irregular periods are common during the first 2–3 years after menarche. However, persistent irregularity may require evaluation.

Menstrual cycles are regulated by a delicate balance of hormones. As a result , disruptions in estrogen, progesterone, LH, FSH, prolactin, or thyroid hormones can lead to irregular periods.

Significant weight changes can disrupt hormone levels often resulting in irregular periods.

Conditions such as anorexia or severe calorie restriction can suppress ovulation, leading to absent or very frequent periods.

Especially without adequate nutrition, can lower estrogen levels or cause amenorrhea (absence of periods). This is common in athletes and dancers.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals in our everyday products can interfere with normal hormones. Some toxins directly affect the ovaries, making it harder for them to release eggs regularly. Common sources of EDCs include;

Perimenopause hormone levels fluctuate as women approach menopause, leading to irregularities in their menstrual cycles.

Starting, stopping, or changing hormonal contraception can cause temporary irregular cycles.

Pregnancy completely stops periods, while breastfeeding suppresses ovulation, often causing irregular or absent periods.

Conditions such as diabetes, autoimmune diseases, liver or kidney disease, or reproductive tract conditions such as endometriosis, uterine fibroid, pelvic inflammatory disease or polyps can affect hormone regulation and disrupt normal bleeding patterns.

medications like steroids, chemotherapy drugs, antidepressants or antipsychotics, among other medications, can interfere with hormone balance.

These are factors like poor sleep, smoking, excessive alcohol use, and substance abuse can also affect menstrual regularity.

Theses are stress that affects the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis, which controls menstruation. The brain controls reproductive hormones and when stress hormones stay elevated, the brain may delay or block ovulation leading to long cycles, heavy bleeding when the period finally comes or light spotting instead of a full cycle.

Gen z has grown up under unprecedented levels of stress

Generally, the menstrual cycle takes up to one-two years to regularize. But from reports, Gen Z women spend more years managing inconsistent menstrual cycles. This increase in time to attain regularity has been associated with adverse health conditions including hormonal imbalance, ovulatory dysfunction, reduced fertility, metabolic complications, and psychological distress.

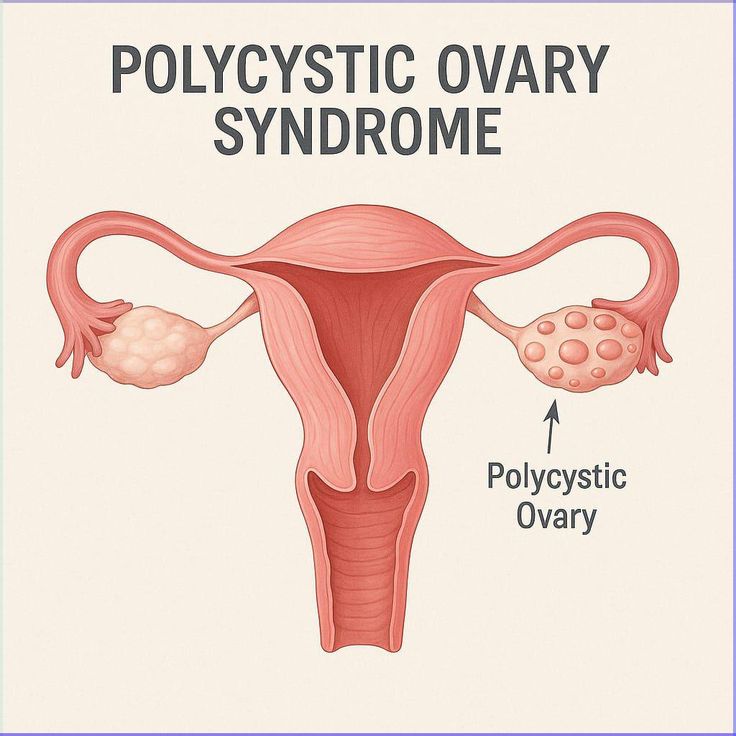

Studies have also shown that early menarche is associated with cancers and metabolic disorders including cardiovascular disease, obesity, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. It is important to understand that early menarche does not directly cause polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), but research shows a strong linkage between early pubertal timing and the later development of PCOS.

Image : Pinterest

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a hormonal disorder that affects girls and women of reproductive age. In the world today, PCOS is one of the leading causes of irregular menstrual cycles and infertility. It involves an imbalance of reproductive hormones that interferes with normal ovulation and metabolism. It is characterized by;

Irregular or Absent Menstrual Periods

Irregular or Absent ovulation

Excess Androgens (Male Hormones), expressed in symptoms such as acne, and excessive facial/body hair (hirsutism).

Rapid weight gain

Darkened skin patches

Polycystic ovaries; this is present in some cases of PCOS. Enlarged ovaries containing many small, immature follicles visible on ultrasound. Despite their name, they are not true cysts.

Although there’s no known cure for PCOS, early identification allows for effective management.

Image: Pinterest

The relationship between early menarche and obesity is bidirectional. In the US and many other countries today, childhood obesity is a fast rising condition. Studies suggest that an increase in BMI can trigger early menarche and the latter, reinforces hormonal patterns such as prolonged estrogen exposure and insulin resistance, which promote further weight gain.

Estrogen is a hormone that influences fat storage and distribution. And a prolonged exposure to it as a result of early puberty causes changes in metabolism and energy balance. Estrogen also increases fat deposition, especially in the hips, thighs, and abdomen.

There is no single cure for obesity. However, early intervention can reduce risk by focusing on balanced nutrition from childhood, regular physical activity, healthy sleep patterns and non-stigmatizing guidance or positive body education for early-maturing girls.

While menstruation itself does not cause heart disease, early menarche reflects early hormonal and metabolic changes including altered lipid metabolism, increased fat accumulation and vascular inflammation over time. These changes elevate the chances of heart disease and stroke in adulthood. The risk increases further when early menarche is combined with physical inactivity, smoking, or poor diet.

Image: Pinterest

During each menstrual cycle, the estrogen causes the endometrium to grow, while progesterone helps regulate and prepare it for possible pregnancy. Early menarche increases the total number of years the uterus is exposed to the hormone oestrogen. Overtime, this prolonged exposure to oestrogen, especially without balance of progesterone, raises the risk of abnormal cell growth and endometrial cancer later in life.

Additionally, early menarche has been associated with a faster depletion of ovarian reserve, meaning the body’s store of eggs may diminish sooner leading to reduced fertility with an increased risk of earlier menopause, shortening the reproductive window for Gen Z women.

Image: Unsplash

Irregular periods for Gen Z women are the body’s early warning sign that something is off. While occasional cycle changes can be normal, persistent irregularity should not be ignored or normalized. Understanding the unique pressures and crises faced by the Gen Z women allows for better education and earlier intervention addressing root causes rather than symptoms alone.

Although the Gen Z period pattern is still under-studied, as awareness grows, the focus must shift toward prevention, early screening or detection, and supportive care. With informed choices, medical guidance, and healthier environments, Gen Z women can take control of their menstrual health, protecting not only their cycles today, but their long-term fertility and overall well-being for years to come.